Virtual Zemlyanka

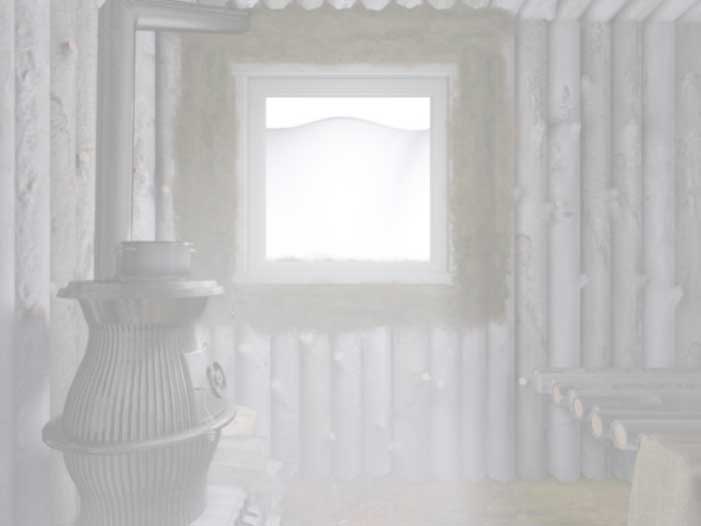

Many Jewish partisans in Eastern Europe lived in underground bunkers called zemlyankas (Russian for "dugout"): small, primitive shelters that provided a living and hiding space, sometimes for dozens of people, even through freezing winters.

Click and drag in the window below to explore a virtual model of Shalom Yoran's zemlyanka that he built and lived in with four other men in the winter of 1942.

Click and drag to start

More About Zemlyankas

What would you do if you had to survive a freezing winter in the woods, with no special tools or materials for building a shelter? What if you didn't want anyone to find you? How would you make your shelter without attracting attention, and then, once you'd built it, how would you disguise it?

Partisans hiding in the forests of Eastern Europe faced these dilemmas. They made shelters they called zemlyankas, from the Russian word for "dugout". Their building materials were taken from the forest itself, and whenever possible, from nearby villages. Careful to hide any evidence of their location, they usually did this work at night.

Eta Wrobel tells how her unit made zemlyankas: “We removed the earth and carried it many kilometers away. Then we would steal the doors to a barn, to make the door. We even moved trees onto the top. If anyone saw us, we had to start again.”

Every one pitched in, racing against time to get the shelters ready. Simon Trakinski recalls: "One time we built a camp from nothing in three days," making bunkers that slept six to people for his group of 200 people. This work had to be done over and over again, as partisans kept moving, one step ahead of their enemies.

Inside the dark bunkers, the hours passed slowly. Simon Trakinski remembers that the only light came from little sticks of burning wood stuck into the earthen walls. The smoke stung his eyes and those of his comrades and soot coated their faces. Eta Wrobel can't forget how hard it was to sleep. Ten or twelve people lay side by side, fully clothed and closely packed to keep warm. “When one person turned, everybody had to turn,” she recalls.

Sometimes the discomfort and, especially, the fear of being closed in was more overpowering than the cold. After Jews who were staying inside a zemlyanka

had been murdered by Polish collaborators, Norman Salsitz resolved to never sleep in a zemlyanka again. “I decided I was not going to go in a bunker…because you couldn't even stand up, you were laying there-and the lice!” Instead he slept outside, burrowed in the snow for warmth.

For most partisans, the zemlyanka was considered a place of refuge from the brutal cold. It was rough and cramped but it kept them alive. The zemlyanka was “as comfortable as possible under the circumstances” says Trakinski, “It could be quite cozy when it was thirty five degrees below zero.” As Wrobel says: “We were glad to have some place to go.”

Excerpts from 'The Defiant'

Listen to Larry King read from Shalom Yoran's book "The Defiant" about partisan life in underground zemlyankas.